A Very London Christmas: The Stories Behind the Traditions

London’s Christmas sparkle is built on centuries of stories — from the Norwegian tree in Trafalgar Square to Victorian crackers, lavish Fortnum & Mason windows, and Dickens shaping "A Christmas Carol" on foggy streets. Beneath the lights and glitter lies a city whose festive traditions grew from history, quirks, and a little magic. Read on to discover the tales behind London’s holiday spirit.

London • Culture • 10 min. czytania

Every year, Londoners marvel at the way Christmas — and all the stuff that comes with it — seems to have started a little earlier. Cue the complaint that “they’ll be putting up the decorations in July next year,” or the confected debate about whether you can even call it Christmas anymore (spoiler alert: you can); and don’t mention the diminishing quality of the ironically named Quality Street boxes of chocolates. Whether the city’s inhabitants like it or not, each year some soon-to-be-D-list celebrity flicks a switch and turns London on to Christmas mode: LED snowflakes, biting weather, carrots and parsnips suddenly on the front bays of the vegetable aisles, and the annual re-emergence of Mariah Carey — seemingly summoned by the first frost.

For visitors, though, London really does possess a wintry charm — the kind you only notice when you haven’t spent much time elbowing through Oxford Circus at rush hour. The markets bustle, the West End glows, and the city leans — sometimes a little too enthusiastically — into festive spectacle. But lurking underneath all the glitter sits something older, stranger, and far more London: the historical quirks and happy accidents that helped shape the modern Christmas — the kind of tidbits our guides love to pull out on walks.

Check out our tours in London -->

So grab a seat by the fire and stick this purple paper crown on your head. London’s festive season isn’t just about what you see in shop windows or hanging over the high streets — it’s also a patchwork of stories, borrowings, and odd traditions the city has gathered over centuries. Some were imported, some were invented locally — and at least one involved a small controlled explosion.

The Trafalgar Square Christmas Tree

One of London’s most famous Christmas landmarks in one of its most famous locations, the Trafalgar Square Christmas Tree takes up its post from the 4th of December till the 5th of January, and this year marks the 79th anniversary of the tradition.

The Norwegian spruce, as the name suggests, comes from Norway — but the history behind it might surprise you. The tree is a gift from the Norwegian people to show thanks for British support during the Second World War. During the Nazi occupation of Norway, both King Haakon VII and his government were based in London in exile. The monarch initially sofa-surfed at King George VI’s home — a little place called Buckingham Palace — before moving further west to Kensington. Haakon made numerous radio broadcasts from Saint Olav’s Norwegian Church in Rotherhithe, where he and his family frequently went to worship. At the end of the war, it was a British battleship that delivered him safely home. The tree, then, stands as a testament to the close friendship and strong bond between the two nations.

Though the Christmas tree as a tradition was popularised in Britain during the mid-1800s, it was in fact a German import. Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert (another German import) famously posed with theirs at Windsor Castle, and the public promptly decided that if it was good enough for the royals, it was good enough for them. The idea soon spread, and before long every respectable household had a spruce jammed into the front room.

Trafalgar Square’s tree, then, isn’t some ancient British custom but a layered one: German roots, Victorian enthusiasm, Norwegian gratitude and modern London spectacle rolled into a single piece of festive diplomacy. Back in 1947, the very first post-war tree needed special permission from the Ministry of Fuel for its lights, thanks to the strict rationing of electricity. This year, by contrast, the lights are more or less guaranteed — switched on in a ceremony at 17:00 on the 4th of December.

Where to go: Erm, Trafalgar Square — but there are plenty of other tall Christmas trees around London, notably in the piazza of Covent Garden and outside the Royal Exchange.

The Christmas Cracker

The traditional Brussels sprout isn’t the only Christmas staple causing big bangs on the 25th of December: every year, British households purchase a staggering 150 million or so decorated — and explosive — cardboard tubes. They’re pulled apart in pairs (it’s a two-person job), unleashing a tiny cloud of smoke, a groan-inducing joke, and occasionally a miniature puzzle or, for reasons known only to the manufacturers, a pair of nail scissors. But where did this strange tradition actually come from?

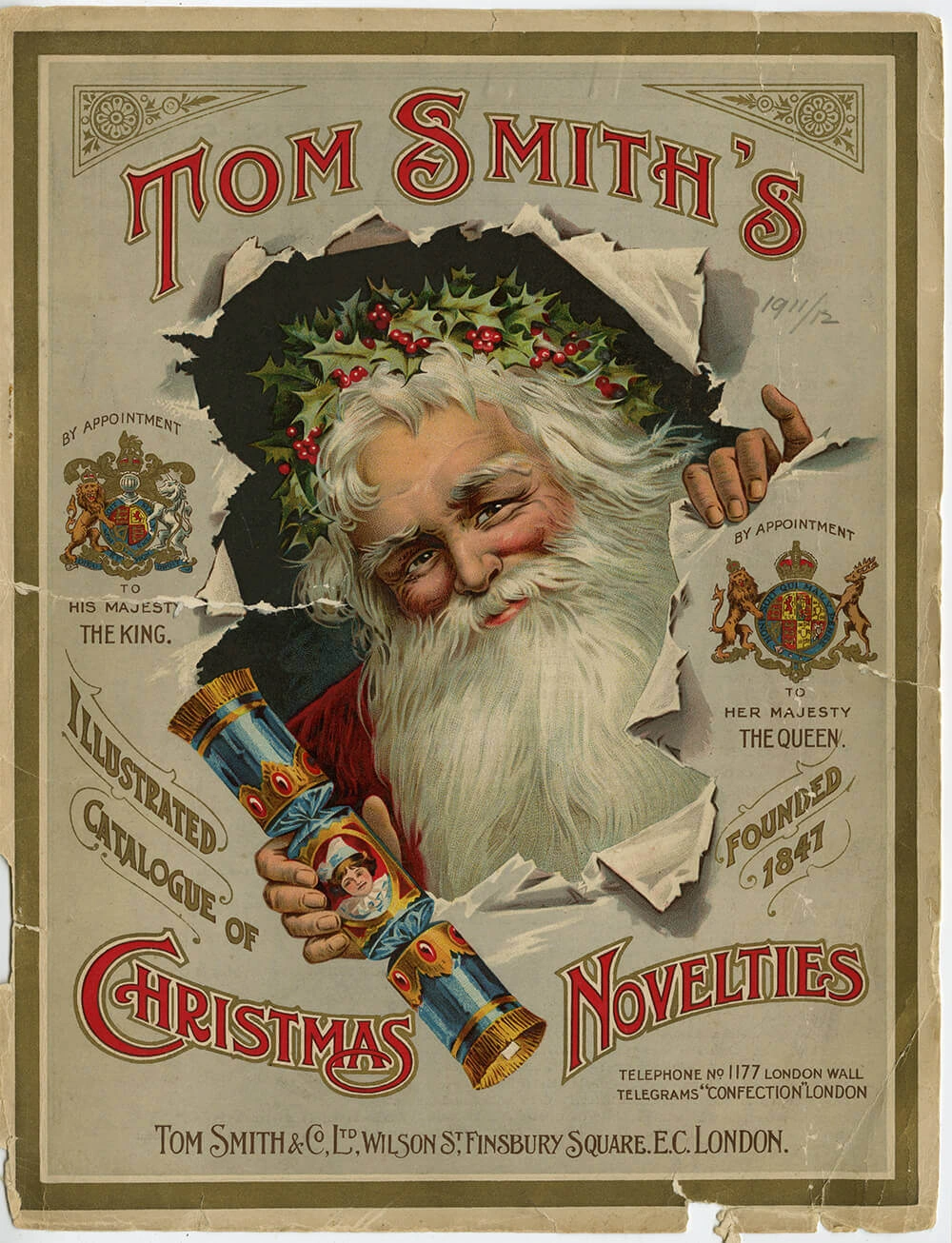

London, of course — and once more it’s the Victorian period (Victoria was on the throne from 1837–1901). Clerkenwell-based confectioner Tom Smith, inspired by a recent trip to Paris, brought the bonbon — a tissue-wrapped sugared almond — to market in Britain in the 1850s. Over the next few years, his idea gradually evolved away from its edible origins. The almond disappeared, replaced with toys and trinkets. Smith then added the “crack” by inserting a narrow strip containing a tiny amount of gunpowder. When two people tug the cracker apart, the friction ignites the strip and produces that satisfying (or alarming) pop.

Christmas crackers also come with the obligatory paper crown worn by begrudging family members up and down the country. This may have roots in older folk customs like Twelfth Night, part of a wider cultural tradition in which hierarchy is inverted for a day and the fool briefly becomes king. Speaking of kings, the Tom Smith Crackers company still exists — and among its many customers is none other than King Charles III himself. The company first received a Royal Warrant in 1906 and still holds one today. Enter any London supermarket, though, and boxes of own-brand Christmas crackers appear in front of you quicker than you can set off a small controlled explosion.

Where to go: Most shops sell Christmas crackers, and they range from expensive sets available in stores like Harrods to more cheap and cheerful options on offer in Tesco; if you’re heading to a pub for Christmas lunch, there will probably be some on the table too.

The Fortnum & Mason Christmas Windows

While shopping might not have been front and centre of Jesus’s message, it certainly defines Christmas now — indeed, the inhabitants of the U.K. spend close to £30 billion a year on gifts. Christmas and consumerism, for better or worse, go ice-skating hand in hand; retail treats the season as a reason to go all out with themed displays and decorations. Of these, it doesn’t get more iconic than the high-end department store Fortnum & Mason and its Christmas windows.

Founded in 1707, Fortnum & Mason began as a grocery store — they famously claim to have invented the Scotch egg! — before expanding to include a more general selection of luxury goods. Like the Tom Smith cracker company, they hold a Royal Warrant, which is why you’ll see a lion and a unicorn above the front door: symbols of England and Scotland from the royal coat of arms. If you spot these two creatures guarding a shopfront, you know that establishment enjoys official royal approval.

Fortnum & Mason has a long and rich association with Christmas — just listen to what Charles Dickens had to say about it in an article published on Christmas Day 1845: “Fortnum and Mason, in Piccadilly, is always a beautiful and astonishing shop, filled with the gourmandizing pleasures of the whole world. Yesterday it was a perfect fairy palace, and Prince Prettyman Paradise of bonbons, and French plums, and barley sugar. Many, many young persons will be ill tomorrow morning if half of those sweetmeats sold yesterday are devoured today.”

From October each year, numerous staff work as hard as Christmas elves to get the iconic window displays ready — and their unveiling always inspires a flurry of press coverage. This year, it’s all unicorns, narwhals, and hard-working field mice set against a backdrop of snow, pine trees, and fireworks. Parts of the display move too: snowflakes rotate, ships sail stormy seas, and mice ride tiny cranes to light Christmas candles.

And some of Fortnum’s displays have even tipped their hat to London’s festive history. Take the 2014 windows, for example, which were themed around the Frost Fayres, the rowdy winter markets that once sprang up on the frozen Thames (mostly during the 17th–19th centuries, with the last in 1814). The river won’t be freezing solid any time soon, but if you want to feel genuinely Christmassy in the present day, Fortnum’s windows remain one of London’s most reliable sources of festive cheer.

Where to go: You’ll find Fortnum & Mason at 181 Piccadilly, and the windows look best in the fading evening light. Other displays worth checking out include Annabel’s, Hamleys toy store, and Cartier.

A Christmas Carol

In the winter of 1843, Charles Dickens and his family had fallen on hard times. His most recent novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, hadn’t sold well and his wife, Catherine, was pregnant with their fifth child. In one of the most striking literary turnarounds, he spent six weeks writing A Christmas Carol and changed the course — and the traditions and atmosphere — of Christmas forever. The book is a striking takedown of miserliness, with the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet To Come showing its central character, elderly businessman Ebenezer Scrooge, the consequences of his selfish ways — and of the striking inequality of Victorian England more generally. Dickens walked for miles through the wintry London nights to help refine the plot, passing slums, debtors’ prisons, and workhouses — all of which fuelled the book’s moral fire. According to his sister-in-law, Dickens was so inspired while writing it that “he wept, and laughed, and wept again, and excited himself in a most extraordinary manner.”

Dickens didn’t pluck his scenes from thin air — they were the London he knew intimately. A Christmas Carol is absolutely soaked in the gloomy atmosphere of Victorian London. The counting houses around Cornhill, the poultry shops of Leadenhall Market, the poorhouses of Camden and Holborn, the fog-drenched courts of the City: all of them seep into the story. That’s partly why A Christmas Carol landed with such force. It wasn’t just a festive tale, but a map of London’s moral geography, challenging its wealthiest inhabitants to notice the people they stepped over on their way home.

The book sold out its first print run in a day. Within weeks there were unauthorised theatre productions, charitable giving ticked upwards, and the phrase “Merry Christmas” was suddenly on everyone’s lips (though its first documented usage came centuries earlier). A Christmas Carol is still a regular festive fixture, whether performed live or shown on television in one of its many adaptations — though everyone knows that The Muppet Christmas Carol remains the definitive version.

Dickens’s London, thankfully, hasn’t disappeared: it’s waiting out there to be walked through and talked about. Though don’t hit the streets expecting an Dickensian-style white Christmas: it hasn’t snowed in the city on the 25th of December since 1999.

Where to go: Wander the narrow lanes around Cornhill, browse through the Victorian splendour of Leadenhall Market or visit the excellent Dickens Museum in Bloomsbury, which occupies the author’s old house. In fact, if you join us on our City of London tour you’ll get a full blast of Dickensian London — and perhaps a cosy pub recommendation for a mulled wine at the end too.

And Finally…

Did you know Christmas was effectively cancelled in London during the mid-1600s? In 1647, a Puritan-dominated Parliament declared that Christmas should “no longer be observed” in England, viewing it as far too extravagant and far too much fun. So if you enjoy Christmas in London this year — the lights, the trees, the markets, our tours and even Mariah’s annual return — spare a thought for those who lived through the season when celebration was officially off the menu.